Reverse Engineering Machines with the Yoneda Lemma

I've decided that the Yoneda lemma is the hardest trivial thing in mathematics, though I find it's made easier if I think about it in terms of reverse engineering machines. So, suppose you have some mysterious machine. You know it's a pure functional Haskell machine (of course) with no funny stuff (no overlapping or incoherent instances or anything like that [1]).

The machine works like this: for some fixed type A, whenever you give it a function of type A -> B it gives you back an object of type B. You can choose B to be whatever type you like, it always works. Is it possible to reproduce the machine exactly after testing it just a finite number of times? Sounds impossible at first, it seems the machine could do just about anything.

Think about how this machine could work. You can choose B freely, and whatever B you choose, it needs to come up with an object in B. There is no way to do this uniformly in Haskell without doing funny stuff. (I'm ruling undefined to be funny stuff too.) So how could this machine possibly generate a B? There's only one possible way, it must use the function of type A -> B to generate it. So that's how it works. It has an object a of type A and when you hand it an f it returns f a. You should also be able to convince yourself that there's no way it could vary the a depending on what f you give it. (Try writing a function that does!) Having narrowed the machine's principle down, it's now easy to figure out what a the machine is using. Just hand it id and it'll hand you back a. So in one trial you can deduce exactly what the machine does (at least up to functional equivalence).

We can specify this formally. The machine is of type: forall b . (a -> b) -> b. The process of extracting the a from the machine, by giving it the identity, can be described by this function:

Given the output of the uncheck1 function, we can emulate the machine as follows:

You're probably wondering why the functions are called these names. See footnote [2] for that. I'll leave it to you to prove that check1 and uncheck1 are inverses to each other.

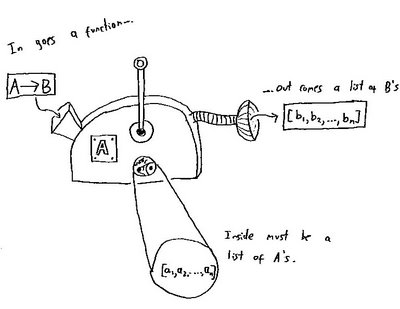

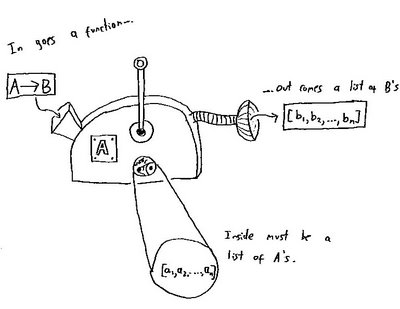

But now there's another machine to consider. This one takes as input a function A -> B and gives you back, not just one B but a whole list full of them. Maybe you're already guessing how it works. If it's generating a bunch of objects of type B then it must surely have a bunch of A's and it must be applying your function f to each one. In other words, the machine's behaviour must be something like this

So if this were the case, how would we determine what a was? How about using the same trick as before:

You should be able to prove that check2 and uncheck2 are mutual inverses.

"But what about this..." you ask, suggesting an alternative definition for the machine:

That has the correct type signature but it doesn't seem to have the same form as machine2. However, with a tiny bit of work we can show it's functionally equivalent to one that does. In fact we can just plug machine2' into uncheck2 and it will give us a list of A's that can be used in machine2. Instead of reverse we could use any function [a] -> [a] and we'd still get a sensible result out of check2. The reason is that if f is of type forall a.[a] -> [a] then f $ map g a equals map g $ f a. (This is a Theorem for Free!.) So we can rewrite machine2' as

which looks just like our machine2. So however we munge up our list to make our machine unlike machine2 we can always 'commute' the munging to the right so it acts on the internal list of A's, converting into a machine like machine2.

One last example:

This time we hand our machine a A -> B and it gives us back another function, but this one is of the type C -> B, for some fixed C. It modifies the 'front end' of the input function so it can take a different argument. How could that possibly work? There's one obvious way: internally the machine is storing a function C -> A and when you hand it your function it returns the composition with the function it's storing.

Here's a potential design for this machine:

Maybe you think there's another type of machine that converts A -> B's to C -> B's. If you do, try writing it. But I think there isn't.

So now we can write the code to reverse engineer machine3:

uncheck3 pulls extracts the internally represented c -> a and check3 makes a functionally equivalent machine out of one.

So...I hope you're seeing the pattern. To make it easier, I'll define some functors:

Now all three example machines have the same form. For some functor f they map a function A -> B to an object of type f B and we deduce that internally they contain an f A. We can now write out versions of check and uncheck that work for all three machines:

The above examples follow when we consider the functors I, [] and ((->) c) (for various values of c) respectively.

Yoneda's lemma is essentially the statement that check and uncheck are mutual inverses. So if you understand my examples, then you're most of the way towards grokking the lemma.

At this point I should add some details. We're working in the category of Haskell types and functions Hask. Expanding out the category theoretical definition of a natural transformation, t between two functors f and g in Hask gives t . fmap f == fmap g . t. In this category, natural transformations correspond to polymorphic functions between functors with no funny stuff so this equality actually comes for free. (To be honest, I haven't seen a precise statement of this, but it's essentially what Theorems for Free! is about.) Yoneda's lemma actually says that for all functors f there is an isomorphism between the set of natural transformations of the type forall b . (a -> b) -> f b and the set of instances of f a. So now I can give proofs:

I'll confirm that check f is natural, ie. that (check f) . (fmap g) = (fmap g) . (check f), although, as I mentioned above, this is automatically true for polymorphic functions without funny stuff.

So that's it, Yoneda's lemma. It's trivial because the isomorphism is implemented by functions whose implementations are a couple of characters long. But it's hard because it took me ages to figure out what it was even about. I actually started with examples outside of Haskell. But Haskell has this weird property that polymorphic functions, with minor restrictions, are natural transformations. (I think this is the deepest mathematical fact about Haskell I've come across.) And as a result, Hask is an excellent category in which to learn about Yoneda's lemma.

I also recommend What's the Yoneda Lemma all about? by Tom Leinster. His presheaf example is the one at which these ideas started making sense to me - but that's because I've spent a lot of time playing with Čech cohomology on Riemann surfaces, so it might not work for everyone. This comment is also worth some thought. In fact, is the Yoneda lemma itself a Theorem for Free?

I haven't said anything about the deeper meaning of the Yoneda lemma. That might have something to do with the fact that I'm only just getting the hang of it myself...

And if you're still confused, let me quote the ubiquitous John Baez: "It took me ages to get the hang of the Yoneda lemm[a]". And nowadays he's one of the proprietors of the n-Category Café!

NB Everything I've said is modulo the equivalence of natural transformations and polymorphic unfunny functions. I may have got this wrong. If so, someone please correct me as I'm sure everything I say here will still hold after some minor edits :-)

[1] Consider the following compiled using GHC with -fallow-overlapping-instances -fglasgow-exts:

f is the identity for everything except for objects of type Int. This is an example of what I call "funny stuff".

[2] The accent on this letter 'č' is called a caron or háček. The book from which I learned about the Yoneda lemma used the caron to indicate the function I call check. I called it that because the TeX command to produce this symbol is \check. This is a multilayered pun, presumably by Knuth. It could just be that 'check' is an anglicised abbreviation for háček. But it's also a characterisically Czech accent so it's probably also an easier (for English speakers) spelling for 'Czech'. And I think it's also a pun on Čech. The caron is used on an H to represent Čech cohomology and so it's also called the 'Čech' accent. (I hope you can read those characters on a PC, I wrote this on a Mac.)

The machine works like this: for some fixed type A, whenever you give it a function of type A -> B it gives you back an object of type B. You can choose B to be whatever type you like, it always works. Is it possible to reproduce the machine exactly after testing it just a finite number of times? Sounds impossible at first, it seems the machine could do just about anything.

Think about how this machine could work. You can choose B freely, and whatever B you choose, it needs to come up with an object in B. There is no way to do this uniformly in Haskell without doing funny stuff. (I'm ruling undefined to be funny stuff too.) So how could this machine possibly generate a B? There's only one possible way, it must use the function of type A -> B to generate it. So that's how it works. It has an object a of type A and when you hand it an f it returns f a. You should also be able to convince yourself that there's no way it could vary the a depending on what f you give it. (Try writing a function that does!) Having narrowed the machine's principle down, it's now easy to figure out what a the machine is using. Just hand it id and it'll hand you back a. So in one trial you can deduce exactly what the machine does (at least up to functional equivalence).

We can specify this formally. The machine is of type: forall b . (a -> b) -> b. The process of extracting the a from the machine, by giving it the identity, can be described by this function:

> uncheck1 :: (forall b . (a -> b) -> b) -> a

> uncheck1 t = t id

Given the output of the uncheck1 function, we can emulate the machine as follows:

> check1 :: a -> (forall b . (a -> b) -> b)

> check1 a f = f a

You're probably wondering why the functions are called these names. See footnote [2] for that. I'll leave it to you to prove that check1 and uncheck1 are inverses to each other.

But now there's another machine to consider. This one takes as input a function A -> B and gives you back, not just one B but a whole list full of them. Maybe you're already guessing how it works. If it's generating a bunch of objects of type B then it must surely have a bunch of A's and it must be applying your function f to each one. In other words, the machine's behaviour must be something like this

> machine2 :: forall b . (a -> b) -> [b]

> machine2 f = map f a where a = …to be determined…

So if this were the case, how would we determine what a was? How about using the same trick as before:

> uncheck2 :: (forall b . (a -> b) -> [b]) -> [a]

> uncheck2 t = t id

> check2 :: [a] -> (forall b . (a -> b) -> [b])

> check2 a f = map f a

You should be able to prove that check2 and uncheck2 are mutual inverses.

"But what about this..." you ask, suggesting an alternative definition for the machine:

> machine2' :: forall b . (a -> b) -> [b]

> machine2' f = reverse $ map f a where a = …to be determined…

That has the correct type signature but it doesn't seem to have the same form as machine2. However, with a tiny bit of work we can show it's functionally equivalent to one that does. In fact we can just plug machine2' into uncheck2 and it will give us a list of A's that can be used in machine2. Instead of reverse we could use any function [a] -> [a] and we'd still get a sensible result out of check2. The reason is that if f is of type forall a.[a] -> [a] then f $ map g a equals map g $ f a. (This is a Theorem for Free!.) So we can rewrite machine2' as

> machine2'' :: forall b . (a -> b) -> [b]

> machine2'' f = map f a where a = reverse $ …to be determined…

which looks just like our machine2. So however we munge up our list to make our machine unlike machine2 we can always 'commute' the munging to the right so it acts on the internal list of A's, converting into a machine like machine2.

One last example:

This time we hand our machine a A -> B and it gives us back another function, but this one is of the type C -> B, for some fixed C. It modifies the 'front end' of the input function so it can take a different argument. How could that possibly work? There's one obvious way: internally the machine is storing a function C -> A and when you hand it your function it returns the composition with the function it's storing.

Here's a potential design for this machine:

> machine3 :: forall b . (a -> b) -> (c -> b)

> machine3 f = f . a where a x = …to be determined…

Maybe you think there's another type of machine that converts A -> B's to C -> B's. If you do, try writing it. But I think there isn't.

So now we can write the code to reverse engineer machine3:

> uncheck3 :: (forall b . (a -> b) -> (c -> b)) -> (c -> a)

> uncheck3 t = t id

> check3 :: (c -> a) -> (forall b . (a -> b) -> (c -> b))

> check3 a f = f . a

uncheck3 pulls extracts the internally represented c -> a and check3 makes a functionally equivalent machine out of one.

So...I hope you're seeing the pattern. To make it easier, I'll define some functors:

> data I a = I a

> instance Functor I where

> fmap f (I a) = I (f a)

> instance Functor ((->) a) where

> fmap f = (.) f

Now all three example machines have the same form. For some functor f they map a function A -> B to an object of type f B and we deduce that internally they contain an f A. We can now write out versions of check and uncheck that work for all three machines:

> check :: Functor f => f a -> (forall b . (a -> b) -> f b)

> check a f = fmap f a

> uncheck :: (forall b . (a -> b) -> f b) -> f a

> uncheck t = t id

The above examples follow when we consider the functors I, [] and ((->) c) (for various values of c) respectively.

Yoneda's lemma is essentially the statement that check and uncheck are mutual inverses. So if you understand my examples, then you're most of the way towards grokking the lemma.

At this point I should add some details. We're working in the category of Haskell types and functions Hask. Expanding out the category theoretical definition of a natural transformation, t between two functors f and g in Hask gives t . fmap f == fmap g . t. In this category, natural transformations correspond to polymorphic functions between functors with no funny stuff so this equality actually comes for free. (To be honest, I haven't seen a precise statement of this, but it's essentially what Theorems for Free! is about.) Yoneda's lemma actually says that for all functors f there is an isomorphism between the set of natural transformations of the type forall b . (a -> b) -> f b and the set of instances of f a. So now I can give proofs:

uncheck (check f)

= (check f) id [defn of uncheck]

= fmap id f [defn of check]

= id f [property of fmap]

= f [defn of id]

check (uncheck f) a

= check (f id) a [use defn of uncheck]

= fmap a (f id) [use defn of check]

= f (fmap a id) [f natural]

= f (a . id) [defn of fmap for ((>>) a)]

= f a [property of id]

I'll confirm that check f is natural, ie. that (check f) . (fmap g) = (fmap g) . (check f), although, as I mentioned above, this is automatically true for polymorphic functions without funny stuff.

check f (fmap g x)

= fmap (fmap g x) f [defn of check]

= fmap (g . x) f [defn of fmap for ((->) a)]

= (fmap g . fmap x) f [property of fmap]

= fmap g (fmap x f) [defn of (.)]

= fmap g (check f x) [defn of check]

= (fmap g . check f) x [defn of (.)]

So that's it, Yoneda's lemma. It's trivial because the isomorphism is implemented by functions whose implementations are a couple of characters long. But it's hard because it took me ages to figure out what it was even about. I actually started with examples outside of Haskell. But Haskell has this weird property that polymorphic functions, with minor restrictions, are natural transformations. (I think this is the deepest mathematical fact about Haskell I've come across.) And as a result, Hask is an excellent category in which to learn about Yoneda's lemma.

I also recommend What's the Yoneda Lemma all about? by Tom Leinster. His presheaf example is the one at which these ideas started making sense to me - but that's because I've spent a lot of time playing with Čech cohomology on Riemann surfaces, so it might not work for everyone. This comment is also worth some thought. In fact, is the Yoneda lemma itself a Theorem for Free?

I haven't said anything about the deeper meaning of the Yoneda lemma. That might have something to do with the fact that I'm only just getting the hang of it myself...

And if you're still confused, let me quote the ubiquitous John Baez: "It took me ages to get the hang of the Yoneda lemm[a]". And nowadays he's one of the proprietors of the n-Category Café!

NB Everything I've said is modulo the equivalence of natural transformations and polymorphic unfunny functions. I may have got this wrong. If so, someone please correct me as I'm sure everything I say here will still hold after some minor edits :-)

[1] Consider the following compiled using GHC with -fallow-overlapping-instances -fglasgow-exts:

> class Test a where

> f :: a -> a

> instance Test a where

> f = id

> instance Test Int where

> f x = x+1

f is the identity for everything except for objects of type Int. This is an example of what I call "funny stuff".

[2] The accent on this letter 'č' is called a caron or háček. The book from which I learned about the Yoneda lemma used the caron to indicate the function I call check. I called it that because the TeX command to produce this symbol is \check. This is a multilayered pun, presumably by Knuth. It could just be that 'check' is an anglicised abbreviation for háček. But it's also a characterisically Czech accent so it's probably also an easier (for English speakers) spelling for 'Czech'. And I think it's also a pun on Čech. The caron is used on an H to represent Čech cohomology and so it's also called the 'Čech' accent. (I hope you can read those characters on a PC, I wrote this on a Mac.)

Labels: haskell, mathematics

5 Comments:

Feynman defined a trivial theorem as one that had been proved.

Thanks for making the Yoneda lemma start to make sense to me.

It seems that :check3 a f" should be "f . a" instead, no?

I have not yet totally understood the Yoneda Lemma but the best introduction I found so far is When is one thing equal to some other thing? by Barry Mazur

單中杰,

You're right. Maybe you can see the cause of my error. I originally wrote the code using fmap to effect the composition as defined later.

Thanks a lot, this is very cool. I am just now reading about the YL in 'Category theory for computing science' and I felt a strong desire to find an explanation in haskell. Would be cool if someone wrote a book on CT with explanations in Haskell, it seems to be often a lot more clear and understandable than standard mathematical notation.

Post a Comment

<< Home