We can write our question a little more formally. Given a type X, can we form a type U with the property that

X2 = U+X

The idea is that the = sign is an isomorphism with the property that the diagonal in X2, ie. elements of the form (x,x), get mapped to the right component of U+X. When we are able to do this, we'll call U the antidiagonal of X, and say that X is splittable.

We can express the relationship between U and X through a multiparameter type class

> diagonal x = (x,x)

> class Eq x => AntiDiagonal u x | x -> u where

> twine :: (x,x) -> Either x u

> untwine :: Either x u -> (x,x)

> twine' :: (x,x) -> u

> untwine' :: u -> (x,x)

> twine (x,y) | x==y = Left x

> | otherwise = Right $ twine' (x,y)

> untwine (Left x) = (x,x)

> untwine (Right y) = untwine' y

The isomorphism between X2 and X+U is given by twine and untwine. But to save writing similar code over and over again, and to ensure we really are mapping the diagonal of X2 correctly, we define these in terms of twine' and untwine'. (Note that twine' is partial, it's only guaranteed to take a value off the diagonal.)

Just to get into the swing of things, here's a simple example:

> instance AntiDiagonal Bool Bool where

> twine' (a,b) = a

> untwine' a = (a,not a)

It's not hard to check that twine and untwine are mutual inverses and that twine . diagonal=Left. You can view this as a special case of 22=2+2 as 2 is essentially a synonym for Bool.

It looks a lot like what we're trying to do is subtract types by forming X2-X or X(X-1). Much as I've enjoyed trying to find interpretations of conventional algebra and calculus in the context of the algebra of types, subtraction of types, in general, really doesn't make much sense. Consider what we might mean by X-1. If X=Bool then we could simply define

data Bool' = False'

This certainly has some of the properties you might expect of Bool-1, such as having only one instance. But it's not very natural. How should we embed this type back in Bool? There are two obvious ways of doing it and neither stands out as better than the other, and neither is a natural choice. But what we've shown above is that there is a natural way to subtract X from X2 because a copy of X appears naturally in X2 as the diagonal. So the question is, can we extend this notion to types beyond Bool?

How about a theorem. (I'll give a more intuitive explanation below.)

Theorem

In any commutative semiring fix a and b. If the equation a2=u+a has a solution, and the equation b2=v+b has a solution, then the equations (a+b)2=x+(a+b) and (ab)2=y+ab also have solutions.

Proof

Simply define

x = u+v+2ab

and

y = au+bv+uv.

QED

So if some types are splittable, so are their sums and products. As types form a commutative semiring we see that this theorem, twined with 12=1+0 allows us to form "X(X-1)" for any type X built purely using non-recursive Haskell data declarations. In fact, we can use the above theorem to define "X(X-1)" for types, and use the notation X2 for this. (I hope your browser shows that the exponent here is underlined.) There's a reason I use this notation which I'll get to later. So (a+b)2=a2+b2+2ab and (ab)2=ab2+ba2+a2b2.

Here's a more intuitive explanation of that theorem above. Suppose u and v are both in Either a b. Then there are several ways they could be different to each other. For example, they could both be of the form Left _ in which case u = Left u' and v = Left v' and u' and v' must be distinct. They could be of the form Left u' and Right v' in which case it doesn't matter what u' and v' are. A little thought shows there are four distinct cases in total. These can be written in algebraic notation as u+v+ab+ba=u+v+2ab. To make this clearer, here's an implementation:

> data Either' a b u v = BothLeft u | BothRight v | LeftAndRight Bool a b

> instance (AntiDiagonal u a,AntiDiagonal v b) => AntiDiagonal (Either' a b u v) (Either a b) where

> twine' (Left x,Left y) = BothLeft (twine' (x,y))

> twine' (Right x,Right y) = BothRight (twine' (x,y))

> twine' (Left x,Right y) = LeftAndRight False x y

> twine' (Right x,Left y) = LeftAndRight True y x

> untwine' (BothLeft u) = let (a,b) = untwine' u in (Left a,Left b)

> untwine' (BothRight v) = let (a,b) = untwine' v in (Right a,Right b)

> untwine' (LeftAndRight False x y) = (Left x,Right y)

> untwine' (LeftAndRight True x y) = (Right y,Left x)

A similar argument can be carried through for (a,b) leading to:

> data Pair' a b u v = LeftSame a v | RightSame u b | BothDiffer u v deriving (Eq,Show)

> instance (AntiDiagonal u a,AntiDiagonal v b) => AntiDiagonal (Pair' a b u v) (a,b) where

> twine' ((a,b),(a',b')) | a==a' = LeftSame a (twine' (b,b'))

> | b==b' = RightSame (twine' (a,a')) b

> | otherwise = BothDiffer (twine' (a,a')) (twine' (b,b'))

> untwine' (LeftSame a v) = let (b,b') = untwine' v in ((a,b),(a,b'))

> untwine' (RightSame u b) = let (a,a') = untwine' u in ((a,b),(a',b))

> untwine' (BothDiffer u v) = let (a,a') = untwine' u

> (b,b') = untwine' v

> in ((a,b),(a,b'))

This all works very well, but at this point it becomes clear that Haskell has some weaknesses. The type Either () () is isomorphic to Bool so we should be able to use the above code to construct the antidiagonal of Bool automatically. But Haskell doesn't give us access to that information. We can't ask, at runtime, if Bool is the sum of more primitive types. There are a number of solutions to this problem - we can use various more generic types of Haskell, or use Template Haskell. But I'm just going to stick with Haskell and manually construct the antidiagonal. (I wonder what Coq has to offer here.)

So I've solved the problem for 'finite' types built from singles, addition and multiplication. But what about recursive types. Before doing that, let's consider an approach to forming the antidiagonal of the naturals. Haskell has no natural type but let's pretend anyway

> type Natural = Integer

There's an obvious packing of a distinct pair of naturals as a pair of naturals:

> instance AntiDiagonal (Bool,Natural,Natural) Natural where

> twine' (a,b) | compare a b == GT = (False,a-b,b)

> | compare a b == LT = (True,b-a,a)

> untwine' (False,d,b) = (b+d,b)

> untwine' (True,d,a) = (a,a+d)

(I had to use compare to work around a blogger.com HTML bug!) It'd be cool if the code above could have been derived automatically, but alas it's not to be. But we can get something formally similar. Define the natural numbers like this:

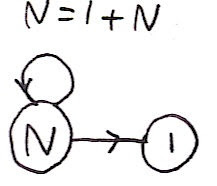

> data N = Zero | S N deriving (Eq,Show)

A natural is zero or the successor of a natural. Algebraically this is just N=1+N. Now we wish to find N2. Using 12=0 and the earlier theorem we get M=12+N2+2N, ie. M=M+2N. Let's code this up:

> data M = Loop M | Finish Bool N deriving Show

> instance AntiDiagonal M N where

> twine' (Zero,S x) = Finish False x

> twine' (S x,Zero) = Finish True x

> twine' (S x,S y) = Loop (twine' (x,y))

> untwine' (Finish False x) = (Zero,S x)

> untwine' (Finish True x) = (S x,Zero)

> untwine' (Loop m) = let (a,b) = untwine' m in (S a,S b)

Note that I've more or less just coded up the same thing as what I did for Either above. Can you see that that this is a disguised version of the code for the antidiagonal of Natural above? Think about the type N=1+N. We can view this as the set of paths through this finite state diagram, starting at N and ending at 1:

Essentially there's just one path for each natural number, and this number counts how many times you loop around. Now consider the same sort of thing with the type M=M+2N, starting at M and ending at 1:

We can describe such paths by the number of loops taken at M, the number of loops taken at N, and a Bool specifying whether we took path 0 or 1 from state 2 to state N. In other words, M is much the same thing as (Bool,Natural,Natural) above! M is a kind of 'compressed' version of a pair of N's. Suppose we want to twine S (S (S Zero)) and S (S (S (S Zero))). Both of these share a S (S (S _)) part. What the type M does is allow you to factor out this part (that's the part that goes into Loop) and the remainder is stored in the Finish part, with a boolean specifying whether it was the first or second natural that terminated first.

Let's step back or a second. Earlier I showed how for any type X, built from addition, multiplication and 1, we could form X2. Now we've gone better, we can now form X2 even for recursive types. (At least for data, not codata.) We haven't defined subtraction in general, but we have shown how to form X(X-1) in a meaningful way.

Let's try lists of booleans next, [Bool]. We can write this type as L=1+2L. Let's do the algebra above to find P = L2:

P = L2

= (1+2L)2

= 12+(2L)2+4L

= (2L2+22L+22L2)+4L

= 2P+2P+2L+4L

= 4P+6L

In other words P = 4P+6L. The easiest thing is to code this up. Remember that each '=' sign in the above derivation corresponds to an isomorphism defined by twine and untwine so after lots of unpacking, and rewriting 4P+6L as 2L+2L+2P+2L+2P we get

> data SharedList = LeftNil Bool [Bool] | RightNil Bool [Bool]

> | HeadSame Bool SharedList | TailSame Bool [Bool]

> | Diff Bool SharedList deriving Show

> instance AntiDiagonal SharedList [Bool] where

> twine' ([],b:t) = LeftNil b t

> twine' (b:t,[]) = RightNil b t

> twine' (a:b,a':b') | a==a' = HeadSame a (twine' (b,b'))

> | b==b' = TailSame a b

> | otherwise = Diff a (twine' (b,b'))

> untwine' (LeftNil b t) = ([],b:t)

> untwine' (RightNil b t) = (b:t,[])

> untwine' (HeadSame a b) = let (t1,t2) = untwine' b in (a:t1,a:t2)

> untwine' (TailSame a b) = (a:b,not a:b)

> untwine' (Diff a b) = let (t1,t2) = untwine' b in (a:t1,not a:t2)

This looks pretty hairy, but it's really just a slight extension of the M=M+2N example. What's happening is that if two lists have the same prefix, then SharedList makes that sharing explicit. In other words this type implements a form of compression by factoring out shared prefixes. Unfortunately it took a bit of work to code that up. However, if we were programming in generic Haskell, the above would come absolutely for free once we'd defined how to handle addition and multiplication of types. What's more, it doesn't stop with lists. If you try it with trees you automatically get factoring of common subtrees and it works with any other datatype you can build from a Haskell data declaration (that doesn't use builtin primitive types like Int or Double).

So now I can say why I used the underlined superscript notation. It's the falling factorial. More generally Xn=X(X-1)...(X-n+1). You may be able to guess what this actually means - it's an n-tuple with n distinct elements. Unfortunately, you can probably see that generalising the above theorem to n from 2 gets a bit messy. But (and this is what I really want to talk about) there's an amazing bit of calculus that allows you to define a generating function (more like generating functor) that gives you all of the Xn in one go. But before I can talk about that I need to write a blog about generalised tries...

Here are some exercises.

(1) Can you code up the antidiagonal of binary boolean trees, T = 2+T2:

data BoolTree = Leaf Bool | Fork BoolTree BoolTree

(2) There are more efficient ways to define the naturals than through the successor function. Can you come up with a more efficient binary scheme and then code up its antidiagonal?

(3) The antidiagonal of the integers can be approximated by (Integer,Integer). This seems a bit useless - after all, the whole point of what I've written above is to split this up. But we can use this approximation to construct approximations of other types where you do get a payoff. Implement an approximation to [Integer]2 this way so that you still get the benefit of prefix sharing. This looks a lot like traditional tries.

"I wonder what Coq has to offer here."

ReplyDeleteIn Coq, the type family of distinct pairs can be defined simply as:

Definition DistinctPair (T: Set): Set := { x: T * T | fst x <> snd x }.

Inhabitants of instances of this family carry with them proofs that the first element is distinct from the second. For example, we can exhibit the inhabitant (1, 2) of the type (DistinctPair nat) as follows:

Definition p12: DistinctPair nat := exist _ (1, 2) (n_Sn 1).

n_Sn is a standard library lemma of type (forall n: nat, n <> S n), and so (n_Sn 1) is a proof that 1<>2.

Eelis,

ReplyDeleteWhat I meant was what does Coq have to offer in terms of generic programming (as in Generic Haskell or PolyP)? Any language that allows constraints on types makes it easy to define the type of distinct pairs. But what I'm really after is a cleaner way to construct the same thing *without* using constraints. For one thing, working out how to do this without constraints led to a general way to compactly represent pairs of structures that have equal substructures. That wouldn't have become apparent if I just used constraints.

Nonetheless, Coq does look interesting and I'll give myself a crash course soon.

This is really interesting stuff. I'm looking forward to the next instalment. It's good see some interest in witnesses to inequality. In Epigram, we sometimes like to present the equality test as a view on two elements of a type: they must be obtained either by duplication, or by projection from what you're calling the antidiagonal. Good name, I think.

ReplyDeleteWe've tended to chop things up a little differently, because we can. We're not exactly aiming for T-1, but rather T-{t} for a specific t:T. Just as category theory eventually stops being lattice theory, type theory eventually stops being combinatorics, more or less at the point where witnesses matter.

As for generic programming, it's not exactly Coq, but I should plug my friend Peter Morris's work on the generic construction of various things in a dependently typed setting, starting with equality decision (informative rather than Boolean). I should also recommend my friend Ulf Norell's new implementation of Agda, which I strongly suspect would be way more fun for this sort of thing than Coq (or Epigram 1, for that matter).

Meanwhile, us Epigram folks have been thinking real hard about how to set up a datatype system which comes with a built-in notion of generic programming. On paper, the operation you seek should jack up more or less directly from the fact that finite enumerations support element removal. (Note that you can't take 1 from 0, but you can remove any z:0 from 0. Of course, you can take 0 from 0*0.)

If A is splittable and (B a) is splittable for all a:A, then (Σa:A. B a) is splittable. Subtracting (a, b) gives you (A-a) + (B a - b). Note that you need an informative analysis method to see this. Suppose you have some (a', b') to compare with (a, b). It only makes sense to compare b' with b if you have identified a' with a.

We're hoping that eventually we'll have enough time to assemble a system from the various experiments we have on the slab. Dependently typed programming relies on informative testing, so 'witness structures' like the antidiagonal do start to show up. In 'The view from the left', James McKinna and I defined element removal for simple type expressions (expressing the pious hope that it might one day be generic), followed by antityped terms (terms with a leftmost type error).

So I should shut up and get on with Epigram 2. But thank you. It's really nice to read posts which I can point to and say 'we should make that stuff just work'. And so we shall.

I'm wondering if the Blogger bug you are referring to is the use of the less-than and greater-than symbols. You should be able to use the character entity < to get < and > to get >.

ReplyDelete"y = au+bv+uv" -- shouldn't this be "av+bu+uv"? Like this:

ReplyDelete(ab)² = y + ab

a²b² - ab = y

(u + a)(v + b) - ab = y

uv + ub + av = y