Consider finite unions of convex bodies in Rn. Write the volume of such a set, A, as v(A). Here are some properties of v:

- v maps finite unions of convex bodies to real numbers.

- v(A ∪ B) = v(A)+v(B) is A and B are disjoint.

- v is invariant under rotations and translations.

These are fairly general properties so an obvious question is this: can any other function, besides volume, satisfy these properties? Hadwiger's theorem says "yes" and shows that in Rn there are n+1 distinct functions, vr for r = 0,…,n and all others are linear combinations of these generalised volumes. vr corresponds to the usual volume and in general we say that vr computes the r-volume. So what are the r-volumes for dimensions less than n?

According to Hadwiger, if R is a closed cuboid of dimensions x1×x2…×xn then its r-volume is the sum of all possible distinct products of r of the xi. For example if n=4 then the 2-volume of the cuboid is given by x1x2+x1x3+x1x4+…+x3x4. The r-volume is simply the product x1x2…xn and the 0-volume is simply 1. But...if you're thinking like I was when I first looked at the article you'll be thinking that this can't make any sense - how can the number 1 represent any kind of generalised volume because it's a constant and hence can't be additive?

Hadwiger's theorem is hard to prove. But for now I'll specialise to 2 dimensions and do just enough computation to show that the generalised volumes do make some kind of sense. And I'll show that the 0-volume turns out to be a variation on a well known topological invariant that you may have seen before.

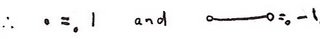

One more bit of preparation. Let me use =r to mean equality of r-volumes.

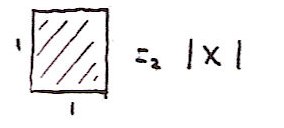

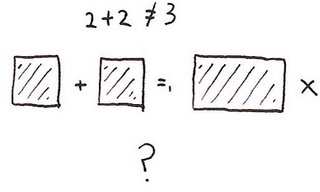

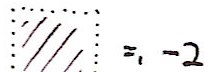

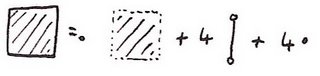

So here's a computation of the 2-volume of a rectangle, R, using v2(R) = x1x2:

Here's the 2-volume of a square:

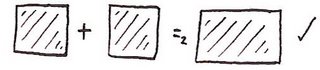

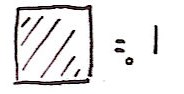

And it's straightforward to see that additivity holds in this case:

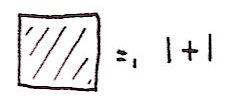

So now consider the 1-volume of a square:

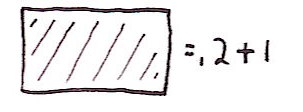

And the 1-volume of a rectangle:

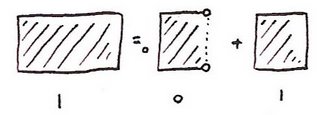

Unfortunately, Hadwiger's theorem appears to be blatantly false if we cut a rectangle in half:

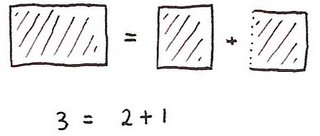

So what's going on? The important thing is that when we cut a rectangle in half we have to choose where the points along the cut go. (For example consider cutting the interval [0,1] in half. We get either [0,0.5)+[0.5,1] or [0,0.5]+(0.5,1].) The way I drew it above the points along this line were getting attached to both of the pieces. So the rectangle wasn't the disjoint union of the two squares I drew. So I'll use the convention that a dotted line around a shape means that the edge itself isn't attached. So we get:

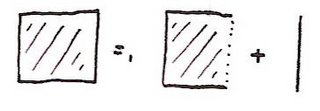

Which allows us to deduce:

and hence from additivity we get

and then

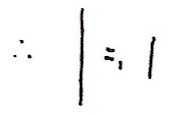

and (with apologies for my scanner's cropping):

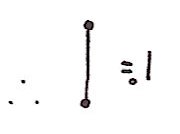

Unlike with the usual 2-volume, infinitesimally thin edges do contribute. But this should lead you to worry about another issue: in the above working I handled edges carefully, but not individual points. Rather than go back and work carefully with edges I'll just say that they don't contribute to 1-volume but they do contribute to 0-volume. So I'll now move onto 0-volume with correct handling of points and I'll leave it as an exercise to rework the above showing that it is actually correct.

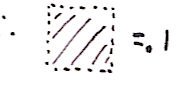

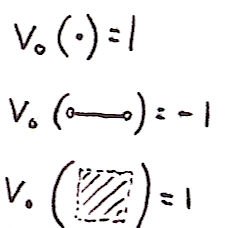

I'm using a small dot to mean the point is included and a small circle to mean a point is excluded. (I hope you can tell a small circle from a zero!) The 0-volume of a closed rectangle is 1. Sounds too trivial to be interesting? Well, from here onwards I think just the pictures will do:

And here's the result I've been aiming for:

In other words, the 0-volume of a closed shape is #vertices-#edges+#faces. Sound familiar? It's nothing other than the Euler characterstic. If it's not familiar, there are countless great articles on the subject out there.

Anyway, to be continued...

Update: Baez talks about some of this stuff here where it's related to Schanuel's characterisation of the Euler characteristic. Yet again I can't write about anything without JB haven't beaten me to it. I could swear that guy's following me around... :-)

No comments:

Post a Comment