A more permanent version of this article is stored at GitHub. Please link to that rather than to here.

If you hadn't guessed, this is about monads as they appear in pure functional programming languages like Haskell. They are closely related to the monads of category theory, but are not exactly the same because Haskell doesn't enforce the identities satisfied by categorical monads.

Writing introductions to monads seems to have developed into an industry. There's a gentle Introduction, a Haskell Programmer's introduction with the advice "Don't Panic", an introduction for the "Working Haskell Programmer" and countless others that introduce monads as everything from a type of functor to a type of space suit.

But all of these introduce monads as something esoteric in need of explanation. But what I want to argue is that they aren't esoteric at all. In fact, faced with various problems in functional programming you would have been led, inexorably, to certain solutions, all of which are examples of monads. In fact, I hope to get you to invent them now if you haven't already. It's then a small step to notice that all of these solutions are in fact the same solution in disguise. And after reading this, you might be in a better position to understand other documents on monads because you'll recognise everything you see as something you've already invented.

Many of the problems that monads try to solve are related to the issue of side effects. So we'll start with them. (Note that monads let you do more than handle side-effects, in particular many types of container object can be viewed as monads. Some of the introductions to monads find it hard to reconcile these two different uses of monads and concentrate on just one or the other.)

Side Effects: Debugging Pure FunctionsIn an imperative programming language such as C++, functions behave nothing like the functions of mathematics. For example, suppose we have a C++ function that takes a single floating point argument and returns a floating point result. Superficially it might seem a little like a mathematical function mapping reals to reals, but a C++ function can do more than just return a number that depends on its arguments. It can read and write the values of global variables as well as writing output to the screen and receiving input from the user. In a pure functional language, however, a function can only read what is supplied to it in its arguments and the only way it can have an effect on the world is through the values it returns.

So consider this problem in a pure functional language: we have functions f and g that both map floats to floats, but we'd like to modify these functions to also output strings for debugging purposes. In Haskell, f and g might have types given by

f,g :: Float -> Float

How can we modify the types of f and g to admit side effects? Well there really isn't any choice at all. If we'd like f' and g' to produce strings as well as floating point numbers as output, then the only possible way is for these strings to be returned alongside the floating point numbers. In other words, we need f' and g' to be of type

f',g' :: Float -> (Float,String)

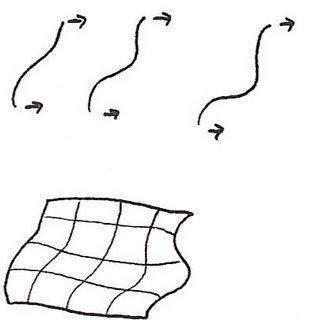

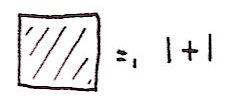

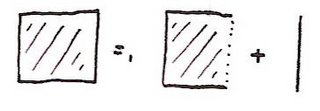

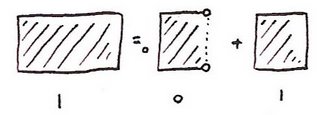

We can draw this diagrammatically as

x

|

+---+

| f'|

+---+

| \

| |

f x "f was called."

We can think of these as 'debuggable' functions.

But suppose now that we'd like to debug the composition of two such functions. We could simply compose our original functions, f and g, to form f . g. But our debuggable functions aren't quite so straightforward to deal with. We'd like the strings returned by f' and g' to be concatenated into one longer debugging string (the one from f' after the one from g'). But we can't simply compose f' and g' because the return value of g' is not of the same type as the argument to f'. We could write code in a style like this:

let (y,s) = g' x

(z,t) = f' y in (z,s++t)

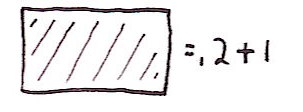

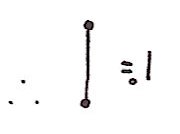

Here's how it looks diagramatically:

x

|

+---+

| g'|

+---+

| \

+---+ | "g was called."

| f'| |

+---+ |

| \ |

| \ |

| +----+

| | ++ |

| +----+

| |

f (g x) "g was called.f was called."

This is hard work every time we need to compose two functions and if we had to do implement this kind of plumbing all the way through our code it would be a pain. What we need is to define a higher order function to perform this plumbing for us. As the problem is that the output from g' can't simply be plugged into the input to f', we need to 'upgrade' f'. So we introduce a function, 'bind', to do this. In other words we'd like

bind f' :: (Float,String) -> (Float,String)

which implies that

bind :: (Float -> (Float,String)) -> ((Float,String) -> (Float,String))

bind must serve two purposes: it must (1) apply f' to the correct part of g' x and (2) concatenate the string returned by g' with the string returned by f'.

Exercise OneWrite the function bind.

Solutionbind f' (gx,gs) = let (fx,fs) = f' gx in (fx,gs++fs)

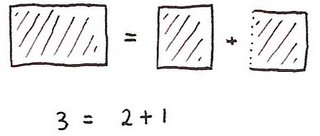

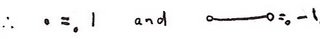

Given a pair of debuggable functions, f' and g', we can now compose them together to make a new debuggable function bind f' . g'. Write this composition as f'*g'. Even though the output of g' is incompatible with the input of f' we still have a nice easy way to concatenate their operations. And this suggests another question: is there an 'identity' debuggable function. The ordinary identity has these properties: f . id = f and id . f = f. So we're looking for a debuggable function, call it unit, such that unit * f = f * unit = f. Obviously we'd expect it to produce the empty debugging string and otherwise act a bit like the identity.

Exercise TwoDefine unit.

Solutionunit x = (x,"")

The unit allows us to 'lift' any function into a debuggable one. In fact, define

lift f x = (f x,"")

or more simply, lift f = unit . f. The lifted version does much the same as the original function and, quite reasonably, it produces the empty string as a side effect.

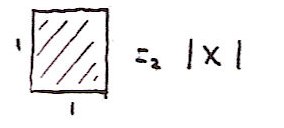

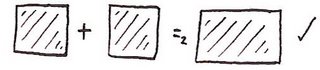

Exercise ThreeShow that lift f * lift g = lift (f.g)

In summary: the functions, bind and unit, allow us to compose debuggable functions in a straightforward way, and compose ordinary functions with debuggable functions in a natural way.

Believe it or not, by carrying out those two exercises you have defined your first monad. At this point it's probably not clear which of the structures we've looked at is the monad itself, or what other monads might look like. But rather than defining monads now I'll get you to do some more easy exercises that will introduce other monads so that you'll see for yourself that there is a common structure deserving of its own name. I'm also pretty confident that most people, faced with the original problem, would eventually have come up with the function bind as a way to glue their debuggable functions together. So I'm sure that you could have invented this monad, even if you didn't realise it was a monad.

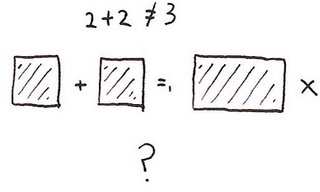

A Container: Multivalued FunctionsConsider the the functions sqrt and cbrt that compute the square root and cube root, respectively, of a real number. These are straightforward functions of type Float -> Float (although sqrt will thrown an exception for negative arguments, something we'll ignore).

Now consider a version of these functions that works with complex numbers. Every complex number, besides zero, has two square roots. Similarly, every non-zero complex number has three cube roots. So we'd like sqrt' and cbrt' to return lists of values. In other words, we'd like

sqrt',cbrt' :: Complex Float -> [Complex Float]We'll call these 'multivalued' functions.

Suppose we want to find the sixth root of a real number. We can just concatenate the cube root and square root functions. In other words we can define sixthroot x = sqrt (cbrt x).

But how do we define a function that finds all six sixth roots of a complex number using sqrt' and cbrt'. We can't simply concatenate these functions. What we'd like is to first compute the cube roots of a number, then find the square roots of all of these numbers in turn, combining together the results into one long list. What we need is a function, called bind say, to compose these functions, with declaration

bind :: (Complex Double -> [Complex Double]) -> ([Complex Double] -> [Complex Double])

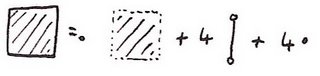

Here's a diagram showing how the whole process looks. We only want to write cbrt' once but still have it applied to both sqrt' values.

64

|

+------+

+ sqrt'+

+------+

+8 / \ -8

+------+ +------+

| cbrt'| | cbrt'|

+------+ +------+

| | | | | |

2 . . -2 . .

Exercise FourWrite an implementation of bind.

Solutionbind f x = concat (map f x)

How do we write the identity function in multivalued form? The identity returns one argument, so a multivalued version should return a list of length one. Call this function unit.

Exercise FiveDefine unit.

Solutionunit x = [x]

Again, define f * g = bind f . g and lift f = unit . f. lift does exactly what you might expect. It turns an ordinary function into a multivalued one in the obvious way.

Exercise SixShow that f * unit = unit * f = f and lift f * lift g = lift (f.g)

Again, given the original problem, we are led inexorably towards this bind function.

If you managed those exercises then you've defined your second monad. You may be beginning to see a pattern develop. It's curious that these entirely different looking problems have led to similar looking constructions.

A more complex side effect: Random NumbersThe Haskell random function looks like this

random :: StdGen → (a,StdGen)

The idea is that in order to generate a random number you need a seed, and after you've generated the number you need to update the seed to a new value. In a non-pure language the seed can be a global variable so the user doesn't need to deal with it explicitly. But in a pure language the seed needs to be passed in and out explicitly - and that's what the signature of random describes. Note that this is similar to the debugging case above because we are returning extra data by using a pair. But this time we're passing in extra data too.

So a function that is conceptually a randomised function a → b can be written as a function a → StdGen -> (b,StdGen) where StdGen is the type of the seed.

We now must work out how to compose two randomised functions, f and g. The first element of the pair that f returns needs to be passed in as an input to g. But the seed returned from the g also needs to be passed in to f. Meanwhile the 'real' return value of g needs to be passed in as the first argument of f. So we can give this signature for bind:

bind :: (a → StdGen → (b,StdGen)) → (StdGen → (a,StdGen)) → (StdGen → (b,StdGen))

Exercise SevenImplement bind

Solutionbind f x seed = let (x',seed') = x seed in f x' seed'

Now we need to find the 'identity' randomised function. This needs to be of type

unit :: a → (StdGen → (a,StdGen))

and should leave the seed unmodified.

Exercise EightImplement unit.

Solutionunit x g = (x,g)

or just

unit = (,)

Yet again, define f * g = bind f . g and lift f = unit . f. lift does exactly what you might expect - it turns an ordinary function into a randomised one that leaves the seed unchanged.

Exercise NineShow that f * unit = unit * f = f and lift f * lift g = lift (f.g)

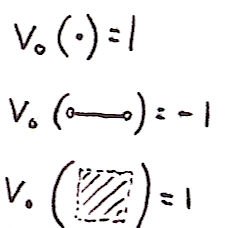

MonadsIt's now time to step back and discern the common structure.

Define

type Debuggable a = (a,String)

type Multivalued a = [a]

type Randomised a = StdGen → (a,StdGen)

Use the variable m to represent Debuggable, Multivalued or Randomised. In each case we are faced with the same problem. We're given a function a -> m b but we need to somehow apply this function to an object of type m a instead of one of type a. In each case we do so by defining a function called bind of type (a → m b) -> (m a → m b) and introducing a kind of identity function unit :: a → m a. In addition, we found that these identities held: f * unit = unit * f = f and lift f * lift g = lift (f.g), where '*' and lift where defined in terms of unit and bind.

So now I can reveal what a monad is. The triple of objects (m,unit,bind) is the monad, and to be a monad they must satisfy a bunch of laws such as the ones you've been proving. And I think that in each of the three cases you'd have eventually come up with a function like bind, even if you might not have immediately noticed that all three cases shared a common structure.

So now I need to make some contact with the usual definition of Haskell monads. The first thing is that I've flipped the definition of bind and written it as the word 'bind' whereas it's normally written as the operator >>=. So bind f x is normally written as x >>= f. Secondly, unit is usually called return. And thirdly, in order to overload the names >>= and return, we need to make use of type classes. In Haskell, Debuggable is the Writer monad, Multivalued is the List monad and Randomised is the State monad. If you check the definitions of these

Control.Monad.Writer Control.Monad.List Control.Monad.Stateyou'll see that apart from some syntactic fluff they are essentially the definitions you wrote for the exercises above. Debugging used the Writer monad, the multivalued functions used the List monad and the random number generator used the State monad. You could have invented monads!

Monad SyntaxI don't want to spend too long on this (and you can skip this section) because there are plenty of excellent introductions out there.

You've already seen how the bind function can provide a nice way to plumb functions together to save you writing quite a bit of ugly code. Haskell goes one step further, you don't even have to explicitly use the bind function, you can ask Haskell to insert it into your code automatically.

Let's go back to the original debugging example except we'll now use the official Haskell type classes. Where we previously used a pair like (a,s) we now use Writer (a,s) of type Writer Char. And to get the pair back out of one of these objects we use the function runWriter. Suppose we want to increment, double and then decrement 7, at each stage logging what we have done. We can write

return 7 >>= (\x -> Writer (x+1,"inc."))

>>= (\x -> Writer (2*x,"double."))

>>= (\x -> Writer (x-1,"dec."))

If we apply runWriter to this we should get (15,"inc.double.dec."). But it's still pretty ugly. Instead we can use Haskell do syntax. The idea is that

do x <- y

more code

is automatically rewritten by the compiler to

y >>= (\x -> do

more code).

Similarly,

do

let x = y

more code

is rewritten as

(\x -> do

more code) y

and

do

expression

is just left as the expression.

We can now rewrite the code above as:

do

let x = 7

y <- Writer (x+1,"inc\n")

z <- Writer (2*y,"double\n")

Writer (z-1,"dec\n")

The notation is very suggestive. When we write y <- ... it's as if we can pretend that the expression on the right hand side is just x+1 and that the side-effect just looks after itself.

Another example. Write our sixth root example in the cumbersome form:

return 64 >>= (\x -> sqrt' x) >>= (\y -> cbrt' y)

We can now rewrite this as the readable

do

let x = 64

y <- sqrt' x

z <- cbrt' y

return z

We're able to write what looks like ordinary non-multivalued code and the implicit bind functions that Haskell inserts automatically make it multivalued.

Inventing this syntax was a work of genius. Maybe you could have invented it, but I'm sure I wouldn't have. But this is extra stuff is really just syntactic sugar on top of monads. I still claim that you could have invented the underlying monads.

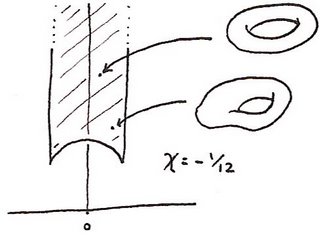

Input/OutputThere's now one last thing we have to look at before you're fully qualified in monadicity. Interaction with the outside world. Up until now everything I have said might apply to any pure functional language. But now consider lazy pure functional languages. In such a language you have no idea what order things will be evaluated in. So if you have a function to print the message "Input a number" and another function to input the number, you might not be able to guarantee that the message is printed before the input is requested! Go back to the randomised function example. Notice how the random seed gets threaded through your functions so that it can be used each time random is called. There is a kind of ordering going on. Suppose we have x >>= f >>= g. Because g uses the seed returned by f, we know for sure that f will generate its random number before g. This shows that in principle, monads can be used to order computations.

Now consider the implementation of random in the compiler. It's typically a C or assembler routine linked into the final Haskell executable. If this routine were modified to perform I/O we could guarantee that the I/O in f was performed before that in g. This is exactly how I/O works in Haskell, we perform all of the I/O in a monad. In this case, a function that conceptually is of type a -> b, but also has a side-effect in the real world, is actually of type a -> IO b. Type IO type is a black box, we don't need to know what's in it. (Maybe it works just like the random example, maybe not.) We just need to know that x >>= f >>= g performs the I/O in f before that in g.

Category TheoryOne last thing. Monads were originally developed in the context of category theory. I'll leave the connection for another day.

Oh...and I ought to mention...I'm still not convinced that I could have invented

Spectral Sequences. But I'm still working on it thanks to Tim Chow.

Appendix: A complete code example using random numbersFirstly, here's the code corresponding to the definitions above:

import Random

bind :: (a -> StdGen -> (b,StdGen)) -> (StdGen -> (a,StdGen)) -> (StdGen -> (b,StdGen))

bind f x seed = let (x',seed') = x seed in f x' seed'

unit x g = (x,g)

lift f = unit . f

So here's what we're going to do: we want to construct a 2 (decimal) digit random number in three steps. Starting with zero we:

(1) add a random integer in the range [0,9]

(2) multiply it by 10

(3) add another random integer in the range [0,9]

Conceptually this operation is a composition something like this

addDigit . (*10) . addDigit. But we know we need to thread the random seed through this code. Firstly, look at the actual definition of addDigit:

addDigit n g = let (a,g') = random g in (n + a `mod` 10,g')

This returns a pair consisting of n+random digit and the new seed. Note how it also takes that extra seed as argument. One could argue that 'conceptually' this function is

addDigit n = let a = random in n + a `mod` 10 and in a suitable strict and impure language that might be considered valid code.

Now consider the operation to multiply by 10. This is an ordinary function that we can 'upgrade' using lift. So we get

shift = lift (*10)

And now is the crucial bit. We can't simply compose but must instead use bind to convert our functions into a form that can be composed. So that conceptual

addDigit . (*10) . addDigit becomes

test :: Integer -> StdGen -> (Integer,StdGen)

test = bind addDigit . bind shift . addDigit

Now we create a seed using my favourite number and run the code:

g = mkStdGen 666

main = print $ test 0 g

Note that I've chosen not to use the Monad type class so that nothing is hidden from you and everything is explicit.

Update: Thanks for the comments. I've now made lots of fixes and added an appendix with a random number example. Most of the code fragments have now been copied back from the final text into real code so there should only be a small number of typos left. Apologies for any confusion caused!

For a slightly different take on monads I've written a little on

Kleisli arrows. And if you're interesting in layering monads to achieve more functionality you can try

this.

Labels: haskell